With essays by Iokepa Casumbal-Salazar, David Uahikeaikalei‘ohu Maile, Dean Itsuji Saranillio, and Noenoe K. Silva

On July 13, 2019, the Royal Order of Kamehameha proclaimed the base of Mauna Kea (aka Mauna a Wākea and Maunakea) – a sacred mountain on the Hawai‘i Island – a sanctuary called Pu‘uhonua o Pu‘uhuluhulu. This action was taken in collaboration with an activist group called Huli – and in broad support of the kiaʻi (protectors) of Mauna Kea. In Hawaiian tradition, during times of conflict, a puʻuhonua is a place designated to provide safety and protection. The recent proclamation by the Royal Order was made in advance of what was to be the start of construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), a $1.4 billion project for an eighteen-story observatory on this mountain that is the highest in the world at 32,000 feet (from seafloor to summit). That same weekend over three thousand individuals gathered at the site, forming a blockade to effectively halt construction trucks from ascending the mountain. At the time of this writing the blockade is still active, and thus far has survived the state governor’s declaration of a “state emergency,” which he issued on July 17 as an excuse to call in the National Guard, along with riot police from several other islands. But the kia‘i are still there, holding steadfast to protect the site.

To give some context to this remarkable resistance front, which has unified a diverse spectrum of the Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) community, this development follows a protracted legal battle lasting over a decade. On October 30, 2018, the Hawai‘i Supreme Court ruled in favor of the TMT and affirmed the Board of Land and Natural Resources’ decision to issue a permit. By June 2019, the governor issued a notice for development to proceed, and announced that construction would commence on July 15, 2019. In addition to desecrating the sacred site, which would also cause gross ecological damage, particularly to the Mauna Kea aquifer, the TMT project is violation of the state of Hawai‘i’s responsibility to manage the “public lands” constituted in part by Mauna Kea and to fulfill constitutional and statutory obligations to Kanaka Maoli.

But looking deeper at the politics of land in the islands, one finds that the “public lands” are illegally expropriated lands; they are the Crown Lands of the Kingdom. The U.S. government itself admitted that these are stolen lands. When the U.S. congress issued the 1993 U.S. Apology acknowledging the illegality of the U.S. backed-overthrow of the Kingdom in 1893, they admitted: “the indigenous Hawaiian people never directly relinquished their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people or over their national lands to the United States, either through their monarchy or through a plebiscite or referendum” (United States Public Law103-150, 103d Congress Joint Resolution 19, Nov. 23, 1993). That language implicitly references both the overthrow and annexation, as well as the fraudulent statehood vote of 1959. Hence, the TMT case must be understood in the legal context of an illegal occupation with a settler colonial overlay.

U.S. settler colonialism in Hawai‘i has meant the historical loss of language and everyday cultural practice as white American culture became hegemonic, cutting us off from knowledge of our own history and ancestors, along with Native spiritual practices. And yet, we see through the indigenous resurgence at Mauna Kea a re-assertion of Hawaiian knowledge and ways of being by the protectors who are engaged in traditional protocols, ceremonies, chant, hula, and song – all guided by the principle of aloha ‘āina (love and stewardship of the land).

This set of short essays on the events unfolding at Mauna Kea all comes from scholar-activists who have been part of the blockade along the way: David Uahikeaikalei‘ohu Maile, “For Mauna Kea to Live, TMT Must Leave”; Iokepa Casumbal-Salazar, “Ceremony and Struggle: The Lāhui at Puʻuhonua o Puʻuhuluhulu”; Dean Itsuji Saranillio, “Stop TMT: Bearing Witness to the Decolonial Change the World Needs”; and Noenoe K. Silva, “Ke Mau Nei Nō Ke Ea O Ka ʻĀina I Ka Pono.”

Each piece centers Hawaiian epistemologies and ontologies to ground a discussion of the resistance efforts of the protectors, and to help readers understand what is at play – and at stake – in the standoff. The role of prophecy and ceremony – calling on deities and ancestral spirits while demonstrating through renewed forms of social organization that show how “another world is possible.” The blockade established to stop TMT is a refusal – but also a collective assertion, in the fulfillment of kuleana (responsibility), to protect Mauna Kea as a sacred site. The rhetoric and rationales for the TMT resembles those deployed over a century ago to try and justify the U.S. occupation and colonial intrusion in ways that resonate with well worn (false) binaries of Hawaiian knowledge / Western science, positioning the protectors of Mauna Kea as standing in the way of “progress” for a fictional universal humanity. Given the state’s prioritized economic forms – tourism, militarism, and construction – we see the TMT in broader context of “development” that is ultimately destructive, unsustainable.

These authors trace the uprising and indigenous resurgence, showing how transformative the collective actions are, and how they have the power to huli, overturn the existing order, by creating meaningful alternatives grounded in indigenous Hawaiian ethics of care and respect, including gender decolonization front and center, backed by our elders with the youth guiding the way. Onipa‘a! Kūʻē!

AUTHOR BIO

J. Kēhaulani Kauanui (Kanaka Maoli) is Professor of American Studies and an affiliate faculty member in Anthropology at Wesleyan University. She is the author of Hawaiian Blood: Colonialism and the Politics of Sovereignty and Indigeneity (Duke University Press 2008); Paradoxes of Hawaiian Sovereignty: Land, Sex, and the Colonial Politics of State Nationalism (Duke University Press 2018); and Speaking of Indigenous Politics: Conversations with Activists, Scholars, and Tribal Leaders (University of Minnesota Press 2018).

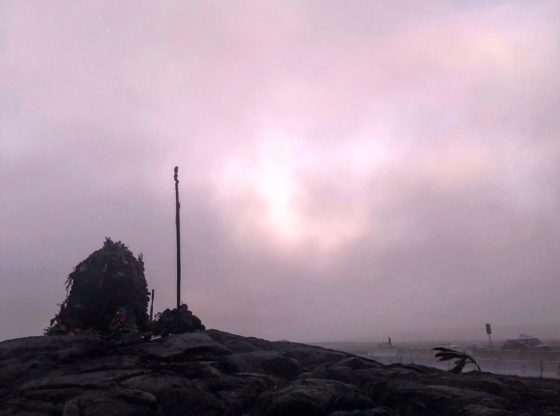

Ahu of the Puʻuhonua o Puʻuhuluhulu at the base of Mauna Kea. Photo by Uahikea Maile

Ahu of the Puʻuhonua o Puʻuhuluhulu at the base of Mauna Kea. Photo by Uahikea Maile