by A.J. Bauer

Editors’ Note: In the past, Radical History Review has run “counter-obituaries” of historical figures in order to challenge the hagiography and whitewashing of crimes against humanity, war-making, and exploitation that frequently pass as obituaries in many mainstream media outlets. For instance, in 1994, RHR published a series of counter-obituaries for Richard Nixon that focused on the nostalgia, omissions, and myths that circulated in the press on the occasion of his death. With The Abusable Past, we hope to revive the counter-obituary in order to reflect on the lives of figures that have had a hand in shaping the world we live in. We are thrilled to relaunch this feature with a counter-obituary of David Koch by scholar of U.S. conservatism, A.J. Bauer. As always, dear reader, we invite you to pitch us ideas at abusablepast@gmail.com

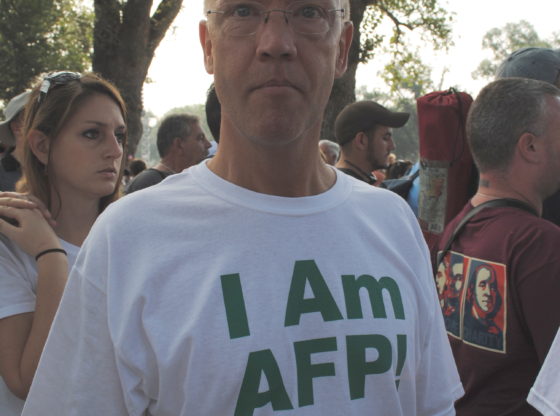

The first time I came across Americans for Prosperity (AFP) in the field was August 2010 — at Glenn Beck’s now infamous reenactment of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

I’d spent that summer attending dozens of Tea Party meetings and rallies in Massachusetts and Texas as part of an ethnography of the movement, plugging in (as many did) through local Meetup groups. I conducted more than two dozen in-depth interviews with self-identified Tea Partiers and gathered an archive box’s worth of ephemera — pamphlets, newsletters, pocket constitutions, bumper stickers, candidate brochures, home-burned CDs with various amateur movement anthems.

Beck’s rally was my final stop before returning to New York to begin writing up, and it was a characteristically motley scene. It attracted a wide constellation of conservative groups that formed or flourished during the early years of the Obama administration — local Libertarian and Republican Party groups, Ron Paul fan clubs, Beck’s 9/12ers, and members of local Tea Parties from seemingly every state (these groups mostly acted autonomously of the national Tea Party organizations, which had declined to formally endorse Beck’s rally).

Also present were members of Americans for Prosperity, identifiable by their “I AM AFP” t-shirts.

I remember noticing the AFP shirts, in part, because after two months in the field it was the first I’d seen of the group. I also made note of them because earlier that week I’d read Jane Mayer’s groundbreaking exposé of the billionaire midwestern industrialists, David and Charles Koch, who bankrolled the group as part of their “covert operations” to counter Obama.

Founded in 2004, with a major initial investment from David Koch in particular, AFP advocated for free market fundamentalism — especially lower taxes and cuts to government spending and regulation that just so happened to align with the business interests of Koch Industries, among the largest privately held corporations in the United States.

Mayer’s extensive reporting on the Koch Brothers, which culminated in the book Dark Money, proved highly influential in shaping the then-still-forming popular common sense of the Tea Party movement — reducing a complex and variegated social movement to the secret machinations of a pair of billionaires.

Her success at seizing the broader Tea Party narrative can be measured, in part, by the massive outpouring of public catharsis at news of the death of David Koch on Aug. 23, 2019 — nine years to the day after Mayer made him famous.

But the overjoyed reaction on left and liberal social media earlier this month underscores the limitations of over-fixating on the agency of movement funders.

After Koch died, I opened my Tea Party archive box for the first time in several years. I found printed ephemera published by the John Birch Society, Young Americans for Freedom, Young Americans for Liberty, the National Center for Constitutional Studies, the Heartland Institute, the David Horowitz Freedom Center, among many other less prominent national and local groups.

Strangely, I hadn’t managed to collect a single piece of AFP material.

Some of these groups, including Young Americans for Liberty, and the Heartland Institute, were at least partially funded by the Charles Koch Foundation. Others, however — John Birch Society and Young Americans for Freedom, for example — long pre-date the Koch brothers’ political activism (although their father, Fred Koch, had been a founding member of the John Birch Society in the late 1950s).

I mention this not to suggest that the Koch-funded organizations have not played a significant role in promoting the modern conservative movement in general, and neoliberal capture of that movement in particular, over the past half century.

Indeed, as many critical David Koch obituaries have pointed out, the Koch brothers’ have invested heavily in campaigns that have proven influential in spreading climate denialism, opposing regulation and campaign finance restrictions on corporations, and supporting a draconian draw-down of social welfare and safety net programs. There is no dismissing the outsized role they’ve played in establishing our current zombie neoliberal dystopia.

Koch and his (still living) brother’s focus on institution-building meant that, aside from an ill-fated run for vice-president on the Libertarian Party ticket in 1980, David remained mostly outside the national public eye. This fact enabled the conspiratorial framing that has come to characterize the Koch Brothers’ reputation in popular culture.

That narrative, popularized by Mayer and many others, has fueled nearly a decade’s worth of progressive fundraising appeals. The Kochs’ arch right-wing villainy has also provided convenient cover for the Democratic Party’s own complicity in the neoliberal project.

Less often acknowledged is the debt this narrative owes to right-wing, anti-Semitic tropes. The Kochs aren’t Jewish, of course. Indeed, their father Fred actively collaborated with the Nazi regime.

But, a reclusive billionaire fomenting unrest against a democratically elected (or otherwise rightfully sovereign) government by paying protestors and investing heavily, and often secretly, in movement infrastructure is literally the right-wing critique of George Soros — the exact same can be, and often has been, said of David and Charles Koch.

The truth is harder to stomach, but thoroughly documented by historians of the modern conservative movement. The Kochs are merely the latest in an intergenerational businessmen’s crusade against Keynesian economic policy and the welfare liberal state in the United States. They are neither the authors, nor even the initial funders, of the neoliberal project.

Furthermore, while that project has been primarily funded and organized by extremely wealthy donors, neoliberal ideology has long managed to resonate across class lines with a wide swath of (primarily, but not exclusively) white Americans.

These conservative grassroots long preceded David Koch’s political activism, and his death will do nothing to stifle their continued growth — just as the deaths of Pierre du Pont, H.L. Hunt, Robert Welch, Jr., Joseph Coors, Richard Mellon Scaife, Sam Walton, and the countless other wealthy funders who contributed to the long neoliberal capture of the modern conservative movement did nothing to stop that movement.

His life, of course, made a sizeable and by all accounts enduring dent in the United States’ capacity for social democracy, not to mention this planet’s capacity for sustaining life. Cheering his end only adds fuel to the fire he spent his life carefully stoking.

What’s left of Koch is now the province of historians, who will do well to remember him as little more than a bit player in a near-century long and ironically collaborative project to promote the neoliberal capitalism that is still choking us all to death.

AUTHOR BIO

A.J. Bauer is visiting assistant professor of Media, Culture, and Communication at New York University, a research fellow at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University, and co-editor of News on the Right.

Unnamed AFP member attending Glenn Beck's "Restoring Honor" rally, Washington, D.C., August 28, 2010. Photo by author.

Unnamed AFP member attending Glenn Beck's "Restoring Honor" rally, Washington, D.C., August 28, 2010. Photo by author.