By Jesús F. Cháirez-Garza

Content warning: This text makes reference to racist stereotypes. While the images are not visible here, there are hyperlinks to some of the images, which are offensive in nature.

The murder of George Floyd and the recent protests in the US surrounding the Black Lives Matter movement have produced a ripple effect throughout the world. Many countries across Latin America, Mexico included, have shown their support to the cause. However, while signs of solidarity are always welcomed, these events have illustrated once again that a majority of Mexicans seem more comfortable supporting anti-racist fights when they occur beyond its own borders. In other words, Mexico thinks of anti-Blackness as a foreign problem that does not relate to its political and social history. But is this really the case? The answer is a hard no and this issue is particularly visible if one takes a look to Mexican popular culture.

Anti-Blackness and racism are topics that are rarely explored in Mexican media. The reasons for this are plenty but perhaps the most important is the nationalist narrative of mestizaje (miscegenation), which has supposedly resulted in the racial unity of all Mexicans. Traditionally mestizaje in Mexico has functioned as tool of inclusion that celebrates the mixture between the Indigenous populations with the Spanish conquistadores. Children learn about mestizaje during their primary school years. Every 12th of October, which marks the day Columbus arrived to the Americas, schools around the country hold assemblies to commemorate ‘el día de la raza’ (day of the race), cementing the colonial encounter as central to race-making in Mexico. Although this day celebrates racial mixture, mestizaje can also be understood as a tool of exclusion that privileges ‘mestizo’ heritage and renders invisible Mexicans who have African, Chinese, Japanese or Filipino origins, among many others. Additionally, by claiming that everyone in Mexico is mixed, mestizaje is often used to negate the existence of settler colonialism, racism and to uphold white supremacist power structures. While there are plenty of stories of how mestizaje has been used to erase and ‘whiten’ the lives of Afro-Mexicans within nationalist narratives (think of the changing portraits of President Vicente Guerrero), here I will examine some recent cases on how anti-Blackness openly operates in Mexican popular culture. To illustrate this, I provide examples coming from publicity campaigns, children’s folk songs, and TV comedy shows.

Like any other country in the world, Mexico lives under a racial code that defines many of the daily interactions that individuals have with other people. Mexicans learn that code from childhood, often without even realizing it, through words and actions that show people where they stand in a society structured through a racial order. Take for example common pet names, such as güera (blonde) or prieta (dark one), used within family circles. Although these terms can be used in a loving and affectionate manner, the people referred to in this way learn how to differentiate themselves on the basis of their skin tone not only in their household but also in their interactions with society in general. These coded racial terms stick to the bodies of individuals and in their minds. Through these codes, people place themselves within a variety of social situations and they can even anticipate the behaviour that others may show towards them.

Racially coded concepts such as güera or prieta acquire greater relevance through their continuous dissemination via popular culture and the media. For instance, despite the notion that everyone is a mestizo, the people represented in Mexican TV shows are overwhelmingly white. Thus, while people with lighter skin might feel included within national life (or aspire to participate in a television program), those with darker skin might feel that their lives and problems are not worthy to be included in popular culture.

Lack of media representation is not the only problem. When the media portrays Black or Brown people, it’s often done through damaging stereotypes in which a darker skin colour is associated with poverty, laziness, or lack of intelligence. An example of this is the recent controversy over the media campaign deployed by the department store Sears in which Indigenous models were used as virtual accessories of ‘stylish’ white women. Yet, stereotypes do not affect everyone equally and, in Mexico, groups with an Indigenous or African backgrounds have been historically the most impacted by this. These negative stereotypes have a long history that can be traced to colonial times. The infamous ‘casta paintings’ of the 18th Century, which attempted to classify and rank the different castes of New Spain according to their blood purity are a good example of this. These paintings show couples of different racial heritage and the offspring resulting from their mix. Everyone in the picture would be tagged with their respective caste so a depiction could claim that the mix from an ‘Español’ and an ‘India’ gives a ‘Mestizo’. These paintings were far from innocent. While white people are portrayed with an elegant couture, Brown or Black people are shown with rags, or are ready to engage in menial labour. Perhaps the most disturbing elements of the casta paintings is that the term used for specific castas implied a regression to a more animalistic life. For instance, the casta painting claimed that the mix between a ‘Chino’ and an ‘India’ gave a ‘Salto Atrás’ (Literally ‘A step back’); while the mix between a ‘Salto Atrás’ and a Mulata’ gave a ‘Lobo’ (a Wolf). In other words, since colonial times people with an African or Indigenous heritage were seen as lesser humans.

Racial stereotypes against Afro-Mexicans are still widespread in popular culture. In a similar case to the recent controversy surrounding the depiction of ‘Aunt Jemima’ by Quaker, the Mexican owned BIMBO, one of the largest baking companies in the world, has been responsible for disseminating stereotypes of Black people as a marketing strategy for at least two of their products — BIMBO’s Toast and Negrito BIMBO (now Nito). This is not a small affair. BIMBO is one of the most powerful companies in the continent and its distribution network reaches most countries in the Americas (US and Canada included), and even Europe. BIMBO’s marketing campaigns are very visible across multiple media platforms. Yet, the way BIMBO has advertised its products is quite problematic and shows how anti-Blackness has gone unchallenged for a long time in Mexico.

For instance, during the 1990s BIMBO began to promote their toasted bread by playing with racist humour. The TV commercials used to promote this product featured an Afro-descendant actor whose presence was used was used as a punchline for a joke. The premise of the publicity campaign claimed that unlike white bread, this new product ‘was born toasted’. The Black actor then delivered the tagline of the product: ‘Bimbo Toasted Bread: The bread that is born toasted, like me’. This was not the only problematic marketing strategy deployed by BIMBO. The advertising associated with the product ‘Negrito BIMBO’, a chocolate covered pastry, also displayed highly offensive racial stereotypes. Once again, during the early 1990s, BIMBO released a TV campaign that featured children in ‘blackface’ on a set full of shacks and huts. This campaign lasted for decades and it was not until very recently that the name ‘Negrito BIMBO’ was replaced by ‘Nito’ (a sort of contraction of the original word). However, instead of abandoning stereotypes associated with Black people altogether, the new marketing strategy created for Nito features a cartoon of a ‘cool’ young man wearing Afro-style hair. The anti-Blackness of these commercials is evident. While the link between BIMBO’S Toast and Black people assumes that whiteness is the norm (since it implies that Brown or Black skin has been ‘overcooked or toasted’), the Negrito BIMBO assigns characteristics of savagery to an entire population.

Stereotypes like the ones used by BIMBO are common in Mexico, however, there is one particular image that stands out above the rest, the Sambo. While the Sambo is mainly associated with U.S. racist iconography, the way in which Afro-Mexicans have been portrayed in the media are almost identical. The iconography associated with the Sambo, usually presents him as a cheeky and happy character despite his enslaved condition. Although the Sambo is an adult man, he is portrayed as a perpetual child: docile, lazy and spending his days eating watermelons. While the Sambo at times could behave in an insolent manner, he was never malicious and it was up to the white man to correct such misbehaviour. In other words, in the Sambo iconography, it’s the white man’s role to become the protector of the masses and the moral compass of society. Similarly, it’s only through the generosity and constant corrections of the white man towards the Sambo that the latter can turn into a good person. Such racial stereotype is one of the classic misrepresentations of Afro-Mexicans. The Sambo stereotype is so widespread that it can be found in the work of children’s song composer Cri Crí, in comic books such as Memín Pinguín (subject of an international controversy) and in popular ‘comedic’ TV characters such as Tomás, portrayed by one of the most famous Mexican comedians in recent history, Héctor Suárez.

Let’s start with the songs written by Francisco Gabilondo Soler, a.k.a. Cri Crí. Soler is perhaps the biggest name in Mexico when it comes to music marketed for children. Despite his passing in 1990, Cri Crí’s albums continue to be sold to this day and his songs are almost always a staple in school festivals. With a catalogue of almost 300 songs, I should clarify that my intention here is not to establish whether Cri Crí was racist or not, rather I will show how anti-Blackness and the iconography of the Sambo have been disseminated in Mexico. Cri Crí has three songs where references to Black people are made: “El Negrito Bailarín,” “Negrito Sandía,” and “La Negrita Cucurumbé.” Of these three melodies, only the last one attempts to normalize Blackness. The central theme of this songs is that ‘Cucurumbé’ should not try to whiten her skin with the waves of the sea as she is beautiful just the way she is. The story with the other two songs is quite different. For example, the song of El Negrito Bailarin (the Little Black Dancer) tells the story of a tin toy that dances by winding it up. The description of the toy (de bastón y con bombín / using a cane and wearing a bombin hat) resembles those of the minstrel shows or the Black Dandy, which made fun of the image of the bodies of Afro-descendants, their customs and their clothing. Despite the fact that he is singing about a toy, Cri Crí attributes the characteristics of the Sambo to the ‘Negrito Bailarín’. The narrator in the song reprimands the toy for his bad behaviour and claims:

‘Hey amigo, lo compré / Hey friend, I bought you

Para verlo bailar a usted / So I could watch you dance

Perozo mueva los pies / Slothful, move your feet

In the ‘Negrito Sandía’ (Watermelon Black Man), Cri Crí uses the image of the Sambo again in a more explicit way. El Negrito Sandía tells the story of a lépero (bad mouthed, rude) character who has to be constantly corrected by Cri Crí. After Cri Crí’s accusation of using a colourful vocabulary, Negrito Sandía is reprimanded by his aunt who whips him with a stick. In the song, this makes Cri Crí laugh:

Con el palo que utiliza / With the stick she uses

El castigo te horroriza / You are horrified of the punishment

Y después de la paliza / And after the beating

Me voy a morir de risa / I will die of laughter

The image of Sambo as the perpetual child is revealed again in one of the song’s final verses. Cri Crí affirms that despite being older, El Negrito will continue with his inappropriate behaviour even when he has to appear in society or attends a formal event:

El día que seas mayor de edad / The day you are of legal age

Si te presentas en sociedad / If you perform in society,

Serás grosero y descortés / You will be rude and impolite

Cuando discutas con un Marqués / When you argue with a Marquis.

Assuming the role of the moral compass of the Negrito Sandía, Cri Crí warns him that he should stop saying nonsense and doing mischief or ‘you will see’ how his punishment goes.

The image of the Sambo, as a badly spoken and rogue character also had a space on prime-time national television through the character of Tomás. Characterized by Héctor Suárez in Blackface style, the character of Tomás took the stereotypes associated with Afro-Mexicans to the extreme. Tomás was not only represented as a poor child from a tropical area, the character was also animalized as his walk (waving his arm above his head) seemed to emulate that of a chimpanzee. Tomás’ sketches revolved around jokes that this character told to his mother (portrayed by another man in drag and in blackface). The formula for the sketches was always the same. Tomás told riddles that were interpreted by his mother as rude jokes or with sexual overtones. However, after being unfairly scolded, Tomás clarified that the riddle had no sexual innuendos and it was his mother, ‘La Negra’, was the one with the problem. This is problematic for at least two reasons. First, Black women are portrayed as hypersexual beings that even confuse an innocent riddle with a dirty joke. Second, the classic punchline with which Tomás clarifies the confusion in the sketch is a denial of his Blackness. After accusing his mother of having a “dirty and filthy mind”, Tomás pronounces his innocence by claiming: “The child is white and pure.” The sketches then suggest that Tomás’s innocent behaviour is so unusual, for the misconceptions that Mexicans have about Blackness that it’s supposed to be funny.

As it can be seen, anti-Blackness in Mexico has been normalised. Racial depictions have been used to keep people in place. To change these attitudes, a critical act of introspection into Mexican culture and popular history is required. Not only explicit racism will have to be challenged, but also the privileges that come with ideas like whiteness or mestizaje will have to be deconstructed. This is particularly important because despite the cruelness of explicit racial stereotypes, perhaps the most dangerous side of anti-Blackness is the erasure of the history of Afro-descendants in Mexico. Without the recognition of such history, racial injustices will go unchallenged. The engagement with these types of representations can open up paths to destroy the structures of privilege by exposing how identities such as Mestizo, Latino, or Mexican are charged with racial meanings. The point is not to compare whether Mexico is more or less racist than other countries, but how to make the country a more just and equitable society for everyone. This of course is not an easy feat, as becoming a true anti-racist is a daily fight against our privileges and our way of life.

AUTHOR BIO

Dr Jesús F. Cháirez-Garza is a Lecturer in the History of Race and Ethnicity at the University of Manchester. He holds a PhD in history from the University of Cambridge. His dissertation focused on the political life of Dr B.R. Ambedkar and the concept of untouchability as a political category. From 2015 to 2018, Jesús was a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Research Fellow at the University of Leeds where he researched the history of pragmatism in Mexico and India. Currently, Jesús is working on an AHRC funded project that investigates that history of anthropology in India. Tweets @GarzaChairez

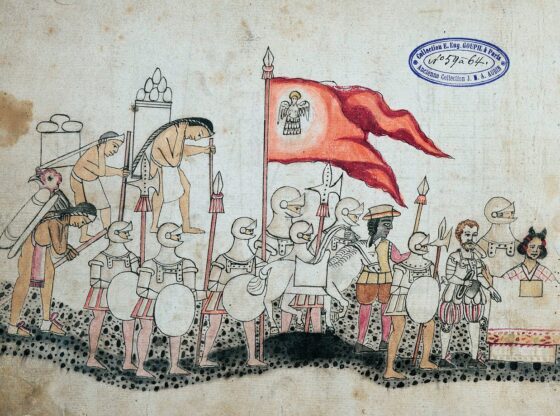

A depiction of the conquest of Mexico in Codex Azcatitlan (early 16th Century). The image shows the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés, the Nahua interpreter Malintzin (Malinche) and the African conquistador Juan Garrido. While Cortés and Malintzin have often been acknowledged as icons of mestizaje, Juan Garrido is hardly ever mentioned in popular historical narratives.

A depiction of the conquest of Mexico in Codex Azcatitlan (early 16th Century). The image shows the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés, the Nahua interpreter Malintzin (Malinche) and the African conquistador Juan Garrido. While Cortés and Malintzin have often been acknowledged as icons of mestizaje, Juan Garrido is hardly ever mentioned in popular historical narratives.