by Sana Khan

My interest in soft powers began somewhat unusually: while researching the Bolshevik feminist Alexandra Kollontai as an overzealous seventeen-year-old historian. Encouraged by my history teacher, I hoped to find out more about women revolutionaries. I visited the Russian Consulate library in my then-home of Mumbai to dig up whatever dirt I could about Kollontai. To my surprise and delight, the dusty library was like a Soviet time capsule, full of sci-fi, revolutionary treatises, and classics. (And nothing at all like Mumbai’s US Consulate library, which I had visited in my capacity as a US citizen, with its shiny security and SAT prep guides.)

While in search of Kollontai, I had stumbled upon a precious Cold War relic. This library was living proof of the cultural relationship between Soviet Russia and socialist India, of soft powers as I defined the term from then on. For me it was both a moment of grace and an adventure story, my first meeting with the serendipity of the archive.

But what I hadn’t considered was how I might be extending this history of soft powers. By stepping into the library, as an adolescent who had almost run out of fingers to count the number of places I had lived, I was positioned as a kind of cultural intermediary. By enterprisingly adapting the sphere of politics to that of school, I reconciled a larger world with the microcosm through which I moved.

The story wasn’t about shifting settings, not exactly, but rather the special language required to create mutual intelligibility. And though hindsight is 20/20, it was not until I encountered the work of Yemeni-American artist Yasmine Nasser Diaz that I believed that history had perhaps not ended before me. Her work offered me a new definition of soft powers that changed the agents entirely.

Diaz depicts young immigrant women like me as cultural diplomats in their everyday interactions. She documents their negotiations in what amounts to an unconventional archive, showing how it can be imaginative, aesthetic, and personal.

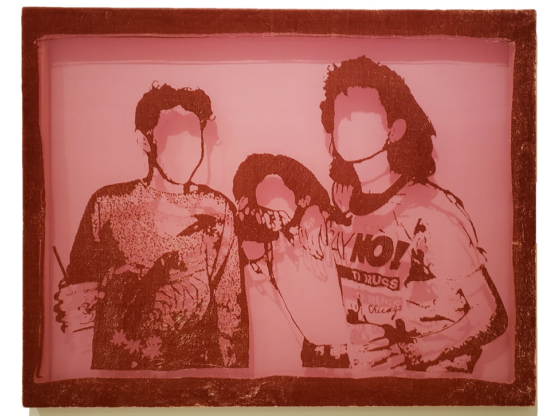

For instance, in her silk-rayon velvet etching “Say No To Drugs,” her subject is three girls hanging out with each other. Two hold takeaway cups. The one in the center drapes her arms loosely on her friends; leans into the frame from a slight distance. The title makes its way onto a t-shirt. A border frames the etching. Another work is a life-size replica of a pastel pink double room. Between the twin beds, color-coordinated coverlets included, is a bedside table with two diaries that belong to a pair of fictional sisters. Crucially, the etching and installation convey nostalgia for a bygone era; a captured memory that embraces the inevitable subjectivity of history.

They are part of Diaz’ art exhibition, soft powers, on view at the Arab-American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, where she was an Artist-in-Residence in March 2020. Her actors are not Cold War era states, but rather young women of the next generation. Their abilities? Soft powers.

“The more layered and complicated your life is, the more nuanced and honed those skills [of diplomacy] become, which is why I think about it as a kind of superpower,” Diaz said to me on the phone.

Narrative is about what you choose to include. So are cross-cultural negotiations. To perform the necessary erasure for a fiber etching, you have to carefully administer an acidic paste that burns away the rayon and reveals the silk underbelly of the fabric. Burn-out fabrics are commonly used to make dir’oo, Yemeni dresses that represent womanhood. To write a diary, to decorate a room, you make aesthetic choices that are ultimately about how you wish to present yourself to the world. Where cultural diplomacy between states tends to be bullishly self-referential, here the self is an art form.

Typically, archives are the lettered traces of states – such as, however unintentionally, in the case of the consulate libraries in Mumbai. Diaz builds an unusual multimedia archive that puts the imagination in service of record-making. The scholar Saidiya Hartman has explored a similar approach, most recently in Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments(2019). While Hartman’s work has initiated a wave of research that imaginatively iterates the past, there is insight that history can draw from the multimedia options of the visual arts, from velvet etching to immersive installation.

Diaz takes ownership of her mediums and asserts them as realms of agentic negotiation–of what is built and broken down; given and concealed. Strategy contextualizes immigrant girlhood. Often friendship is the driving force of soft powers, helping to unfold girls’ agency. Diaz is more interested in the interpersonal realm than making the girls symbols of entire cultures. Clues about life in the 90s come through their fashion choices and the solace that they find among other young immigrant women.

In the fiber etching “Thick as Thieves,” three girls pose together. In “Noxzema and Lipliner,” a girl applies lipliner while acne cream sits in front of her. In “Truth or Dare,” one girl moves close to another, possibly whispering something in her ear. These are based on teenage photographs of herself and her friends. Their poses, so different than my own millennial, Internet-saturated camera anglings, bear a distinct time stamp. “The photos I used each displayed a sense of camaraderie and sisterhood,” Diaz said.

Diaz has an interest in coming-of-age stories and enlisted Randa Jarrar, author of the young adult novel A Map of Home (2008), to write the sisters’ diaries. Though this is the third version of the installation, it is the first one with diaries. These weave together the written and imagined and add to the artist’s archive of girlhood. They further illustrate the richness of source material to be found in the ephemera of daily life.

Even in the fiber etchings of girls alone, the sense that they speak a shared language comes through. These pieces highlight an animating friction of the show, that between collectivism and individualism. “Girls from immigrant families who migrated from the global south to the global north can experience a specific kind of tension that I’m really interested in exploring and understanding more, between collectivist and individualist cultures,” Diaz told me.

She mentioned that she chose not to fill in details of faces to preserve anonymity and to reference the censorship of women’s images in sections of the Arab world. “I’m also circumventing the censorship for my own reasons, as a layer of protection and privacy,” she clarified. That’s another motivation behind making the sisters fictional.

“Assuring them that they will remain anonymous allows them to share more with me. It’s a way of crossing this threshold of personal space into the public realm.”

Diaz deliberately occults, fictionalizes, and combines her sources to convey her message. This approach, anathema to typical historical practice, suggests other, more creative, expressions of the past.

When it comes to the two sisters, Diaz wanted to show the complexity of young immigrant women. For instance, she is far from being deterministic about the relationship between faith and personality. She said, “the conservative one has a crush on a boy and she has a pregnancy scare, or she thinks she does, and the older sister who is more overtly rebellious in how she talks in her diary writes about how much she loves cooking with her mom.” As immigrants, their social negotiations are dynamic, and do not fit in with preconceived notions.

Conversation plays a large role in this project. Diaz talked about how there is always one person in group discussions who speaks up and who you then feel grateful for and how she wanted to be that person through her work. “It was important to me that through the lens of these teenage sisters, we learn how much is on a young girl’s shoulders,” she said.

She also seeks to provide a space where Arab women can speak candidly and without judgment. “I want to dissect these things that we go through but I don’t want to contribute to the demonization of our community,” she said.

Of course, the Covid-19 pandemic has interfered with the display of and programming around the show. To address this, Diaz made a video of the exhibition. She also participated in an initiative called Drive-By Art in LA, where she hung the fiber etchings in between trees. The effect was profound: “They were hanging on a string as if on a clothesline, blowing freely in the wind with the sun shining on them. It was really lovely.”

Seeing how Diaz imbues soft powers with life beyond the machinery of national regimes doesn’t change who the main characters are. It finds them, puts them center stage, makes them into art, gets you reckoning with them. In redefining the protagonists, Diaz reimagines what an archive can be and do. And as I think back to my own peripatetic girlhood, it helps me locate moments of strength and ability – of soft powers. By the age of eighteen, I had lived in eight different places around the world and was immersed in five languages. I was a cultural agent as much as, and more than, any state. I take my terminology from Diaz.

AUTHOR BIO

Sana Khan is a writer and editor based in New York (move #13, give or take!). She owes a real debt to her high school history teacher, Mr. Clinton.