By Amaury Rodríguez

Since the worldwide political upheavals of the 1960s, Caribbean and Latin American social scientists have expanded the production of people’s history or history from below by rescuing collective memories and ways of life relegated to the margins by traditional historians. Radical historians, sociologists, philosophers, activists, artists and writers have placed premium importance on the reconstruction of a history from below counterpoise to the official history and grand narratives focused on heroic figures championed by white Creole elites in Abya Yala, or the Americas. This has taken the form of, for instance, investigating the popular thinking rooted in the indigenous people of the hemisphere and Africa or researching women’s history and resistance to slavery and colonialism.[1] In the Dominican Republic, this cultural shift materialized after the fall of the Trujillo dictatorship in 1961, giving birth to a radical historiography whose main objective is to lay down the foundation of an ongoing scientific-based inquiry into the Dominican past that continues today.[2]

The Trujillo regime (1930-1961), a direct outgrowth of the first U.S. military occupation (1916-1924), left a legacy of authoritarianism, machismo, pseudo-scientific racism, and anti-Haitian racism. The Trujillato’s rabid nationalism, among other factors, led to the 1937 massacre of Haitians, Black/Afro-Dominicans, and Dominicans of Haitian origin. Nonetheless, solidarity ties between the two people that share the island of Hispaniola continued unabated. In “Looking for Solidarity,” translator, author, and scholar Sophie Maríñez reminds us of the long tradition of Haitian-Dominican solidarity by surveying the legacy of Jacques Viau Renaud, the Haitian-born poet and revolutionary martyr who died fighting in defense of Dominican sovereignty during the second U.S. invasion in 1965. Maríñez recounts how “Viau joined the rebel unit Comando B-3, and soon became a sub-comandante, but died, hit by a mortar, when he was only twenty-three. Hundreds of people attended his funeral. Although Dominicans had already adopted him as one of them, Constitutionalist president Francisco Caamaño formalized this adoption by issuing a decree granting him posthumously Dominican nationality for defending with his life the nation’s democracy and sovereignty.”

In thefirst years of the post-dictatorial period (1961-1965), middle- and working-class Dominicans influenced by the Cuban revolution joined reformist and revolutionary movements, while a nascent counter-culture amplified the revolutionary spirit of the era. Yet, the Dominican peoples’ democratic aspirations were curtailed by another brutal American military occupation. In April of 1965, a democratic revolution seeking to restore President Juan Bosch to power, after his government was overthrown by a U.S.-backed right-wing military coup two years earlier, raised alarms in Washington. Four days later, President Lyndon B. Johnson sent American troops to Santo Domingo, crushing the popular revolt after months of fighting. Afterwards,Joaquín Balaguer’s U.S.-backed right-wing regime (1966-1978) carried out a genocidal campaign against the revolutionary Left. Despite state repression, the revolutionary culture created during the 1960s thrived in the barrios and in the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo (Autonomous University of Santo Domingo, UASD), the public university and epicenter of left-wing activity. Popular education projects like clubes culturales y deportivos (cultural and sport clubs) sprung up, and activist-scholars founded social research units at UASD. By the 1970s and early1980s, a Marxist historiography coalesced around Communist partisan periodicals like Impacto Socialista and critical left, independent Marxist journals like Nuevo Rumbo, Realidad Contemporanea and Poder Popular. Left-wing historiography and counter-cultural ideas also appeared in mainstream publications that ran the gamut from newsweekly magazines like ¡Ahora!and Renovación to suplementos culturales (culture sections) of widely-read daily newspapers.Further, street theater left its mark on popular education and Dominican Blackness as documented by scholar and translator Raj Chetty in the article“‘La calle es libre’: Race, Recognition, and Dominican Street Theater.” Finally, the Siete dias para el pueblo(Seven Days for the People)music event in 1974 internationalized the campaign to free political prisoners, rescued Afro-Taino culture, reinvigorated popular music, and set the tone for Dominican—and hemispheric—protest music for the ensuing decades.

The following microsyllabus is a partial introduction to radical perspectives within Dominican historiography. Given the prevalence of colonial violence, right-right ideology, racism, ethno-nationalism, obscurantism, capitalist exploitation and oppression on a local and global scale, the revolutionary lessons from the 1960s Dominican counter-culture still resonate deeply with activists, educators, cultural workers and artists whose research and public interventions challenge reactionary notions of nationhood and self, and ultimately, the status quo. A Further Reading section to complement sources in Spanish appears at the end. I hope that this microsyllabus will introduce students, scholars, translators, artists, activists, librarians, archivists, and the general public to Dominican history from below by engaging with saberes locales (local knowledge) produced by both Dominicans and non-Dominicans on the ground.

Emilio Cordero Michel, La revolución haitiana y Santo Domingo [The Haitian Revolution and Santo Domingo], Santo Domingo: Ediciones UAPA, 2000.

First published in 1968, this book introduced an entire generation to a historical materialist framework on the Haitian revolution and its long-lasting impact on the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo (modern day Dominican Republic). Characterizing the Haitian revolution as a “democratic revolution” and placing it within the international capitalist revolutions against feudalism, Michel highlights the revolution’s impact on an embryonic Dominican society, resulting in examples of social and political progress like the first abolition of slavery in 1801 and the introduction of a new legal system that gradually contributed to the decline of colonial order in the following decades. In a critical assessment devoid of hagiography, Michel narrates the negative consequences of the Napoleonic counter-revolution against the Haitian revolutionaries—the site of which was the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo—while pointing out the missed opportunities by certain sectors within the Haitian revolutionary leadership to unify the island as a bulwark to European imperialism. In dialogue with the Haitian Marxist intellectual Gérard Pierre-Charles and others, Michel assails white Dominican elite intellectuals for harboring class hatred and racial prejudice against Haiti, constructing a racist corpus, and planting the seeds that perpetuate the falsification of history that serve the interests of ruling class sectors to sow division between the two peoples that share the island of Hispaniola.

Lusitania Martínez, Palma Sola: opresión y esperanza [Palma Sola: Oppression and Hope], Santo Domingo: Ediciones CEDEE, 1991.

Mass killings are intrinsic to the repressive apparatus of the modern Dominican capitalist state. On December 28 of 1962, during the last day of the Consejo de Estado [State Council] transitional government, the Trujillist army conducted a massacre in the town of Palma Sola in San Juan de la Maguana province killing over one hundred people and wounding an unknown number including women and children. The sheer savagery displayed by the army preceded a campaign in the press portraying followers of Olivorio Mateo as anti-Christians who engaged in brujeria [witchcraft]. Olivorio Mateo was a Black Dominican spiritual leader who led peasant guerillas in the resistance against the first U.S. occupation military occupation (1916-1924). Exploring the religious doctrine of this messianic Afro-Dominican movement, Martínezsheds lights on cultural, religious, and political continuities and cimarronajes silenced by elite historians at the service of the Dominican state.

Roberto Cassá, Movimiento obrero y lucha socialista en la Republica Dominicana (desde los orígenes hasta 1960) [Socialist Struggle and the Labor Movement in the Dominican Republic from its early beginnings to 1960], Santo Domingo: Fundación Cultural Dominicana, 1990.

Cassá, aformer combatant of the 1965 revolution, reconstructs the history of working-class radicalism in a monumental book that traces the origins, history and trajectory of “the gravediggers of capitalism” and the Dominican counterpart of the international socialist movement from the nineteenth century until 1960. Cassá’s brief history of the Partido Socialista Popular (Socialist Popular Party, PSP), modeled after Cuba’s PSP and forerunner to the Communist Party, is essential reading. As important is Cassá’s take on the successful 1946 sugar strike in the midst of the Trujillo dictatorship. Led by Afro-Dominican labor leader Mauricio Báez and others, native and foreign workers of Haitian and West Indian origin shook the foundations of the Trujillato by defying state repression and winning their demands.

Julio Cesar Mota Acosta, Los cocolos en Santo Domingo [The West Indians in Santo Domingo], Santo Domingo: Editorial La Gaviota, 1977.

This is a brief history of the English-speaking Afro-Caribbean West Indian community in the Dominican Republic, which populated the Eastern part of the country. During the early twentieth century, West Indians (known as ingleses or cocolos) arrived in the Dominican Republic as part of a migration wave spurred by the need for temporary skilled laborers in the booming foreign-owned sugar industry. Acosta summarizes some of the customs and social institutions brought by West Indian immigrants such as mutual aid societies, protestant churches, funeral homes, and sport associations. The book also highlights the poetry of Norberto James Rawlings (1945-2021) whose poem “Los inmigrantes” (The Immigrants), included in the book, is a seminal document of Afro-Caribbean political and cultural affirmation. With this book, Acosta helped demystify the white elite’s categorization of Dominican society as a homogeneous, Roman Catholic Spanish-speaking nation.

Celsa Albert Batista, Mujer y esclavitud en Santo Domingo [Women and Slavery in Santo Domingo], Santo Domingo: Ediciones Cedee, 1990.

The book starts with a dedication to Mamá Tingó, the Black peasant leader killed during the Balaguer regime. The book dedication is a clever and radical political gesture that pays homage to Tingó’s legacy of struggle and serves as a reminder of the institutionalized racism, patriarchal violence, Afrophobia, and colonialist dispossession that exist within Dominican society. Published in the context of growing resistance to the unpopular commemoration of the Spanish conquest in 1992 by the Dominican state, this book puts gender, race, and class at the center of the study of the institution of slavery in the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo or Quisqueya. Reviewing the impact of colonial-era laws on enslaved African women, Batista, a Dominican of West Indian descent, sheds light on domestic work, cimarronaje (marronage), the role of women in the manieles (maroon communities), sexual objectification, and African women’s resistance to slavery.

Marivi Arregui, “Trayectoria del feminismo en R.D” [The Trajectory of Feminism in the Dominican Republic], Ciencia y Sociedad 1.13 (1988): 9-17.

Arregui put together a sharp and condensed informative research article/report on Dominican feminist organizations from 1961 to 1980. After tracing the middle-class origins of Dominican feminism, Arregui transitions into the politization of feminism with the founding of the left-wing Federación de Mujeres Dominicanas (Dominican Federation of Women, FDM) at the onset of the post-dictatorial period in 1963. Arregui also looks at the mobilization of working-class women outside traditional feminist organizations in the 1970s, left wing fractionalism and its negative impact on the cohesion of women’s organizations, and feminist publications.

Carlos Esteban Deive, La esclavitud del Negro en Santo Domingo (1492-1844) [The Enslavement of Black People in Santo Domingo], Santo Domingo: Museo del Hombre Dominicano, 1980.

This dense, two-volumeinterdisciplinary undertaking by a Spanish-born Dominican historian and Africanist is an invaluable contribution to radical Dominican historiography. Deive discusses the origins and trajectory of the institution of slavery, the role of the Catholic Church in the slave trade, slave revolts, ethnic origins of enslaved Africans, racism, manumission, and ideological constructs during the colonial period. Further, Deive charts a chronology of events that led European colonizers to the eventual replacement of the enslaved indigenous Taino people by African people. Moving across the fields of social science, these two tomes engage the reader in a tour de force that opens new vistas into the history and culture of African people, pre-capitalist formations, colonial-era thought to European monarchic systems, and Orientalism, among others themes.

Margarita Cordero, Mujeres de abril [Women of April], Santo Domingo: CIPAF, 1985.

Written by an independent journalist and feminist, this is a well-documented overview of the role of women during the 1965 revolution and U.S military occupation. Throughout the book, Cordero commits herself to eschewing hagiography as she investigates the impact of the armed conflict on women, notions of revolutionary heroism, machismo, sexism, and the masculinization of the left. In interviews with left-wing militant and non-militant women from different social strata, Cordero amplifies the voices of women long silenced by male historians. Published by the Centro de Investigación para la Acción Femenina (Research Center for Feminist Action, CIPAF), a feminist NGO, this book shies away from idealized notions of revolution to tell a history of a tumultuous time with women at the center, making a critical contribution to the history of radical movements and women’s history.

Alejandro Paulino Ramos, Vida y obra de Ercilia Pepín [Life and Work of Ercilia Pepin], Santo Domingo: Editora Universitaria-UASD, 1987.

The role of women has been crucial in nationalist resistance to U.S. imperialism in the Caribbean as this biography of educator, feminist, suffragist, and author Ercilia Pepín illustrates. Pepín publicly opposed the first U.S. military occupation of the Dominican Republic, and as an internationalist, she took part in the region-wide solidarity campaign to aid Augusto Cesar Sandino’s anti-imperialist army during the U.S occupation of Nicaragua. Ramos also highlights Pepín’s contribution to education reform rooted in the ideas of the Puerto-Rican born educator and Antillanist Eugenio María de Hostos, whose secular and scientific-based education reforms in Quisqueya were wiped out by the conservative Trujillo dictatorship.

José A. Moreno, Barrios in Arms: Revolution in Santo Domingo, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1970.

Cuban-born sociologist Moreno was a witness to the 1965 revolution in the Dominican Republic and from that first-hand experience constructed a sociological profile of the popular revolt. In April of 1965, working-class neighborhoods (barrios) became bastions of rebellion where ordinary people—mainly people of African descent, LGBT people, and women—re-organized their communities through comandos populares (civil-military units). In this engaging book, Moreno documents spontaneity, political consciousness, tigueraje (street philosophy), and the fleeting lives of barrio dwellers fighting for survival.

Dagoberto Tejeda Ortiz, Cultura popular e identidad nacional [Popular Culture and National Identity]. Santo Domingo, República Dominicana: Consejo Presidencial de Cultura/Instituto Dominicano de Folklore (INDEFOLK), 1998.

This is a two-volume collection of short essays by a Dominican sociologist trained in Brazil during the 1960s. In the 1970s, Dagoberto (as he is popularly known) was a member of the Comites Revolucionarios Camilo Torres (Camilo Torres Revolutionary Committee, or CORECATO) and member of the musical group Convite. This book is a compendium of Dominicanpopular practices and identity markers— a rather unique religious, social, and cultural set of customs that has as its main elements African death rites, Catholic saint worship, and creolized Hispanic customs. Other themes in the book include racism, negative stereotypes about Haitian immigrants, slave revolts, as well as urban popular culture in Borojol, a Black working-class neighborhood that emerged during the Trujillo dictatorship.

Quisqueya Lora Hugi, “El sonido de la libertad: 30 años de agitaciones y conspiraciones en Santo Domingo (1791-1821)”,Clio 182 (2011): 109-140.

The fight against the colonial order and the institution of slavery in the former Santo Domingo Español (Spanish colony of Santo Domingo) has been often overlooked by elite historians who were, in numerous instances, colonial officials, slave masters and allies of tyrannical regimes. In this article, Lora Hugi examines two different periods in time shaped mostly by the Haitian revolution taking place in the neighboring French colony of Saint Domingue by charting a chronology of slave revolts led by enslaved African people in the Spanish colony from 1791 to 1802, and rebellions led by urban sectors of society (including former slaves and mulattoes) from 1809 to 1821. These dates are crucial in the understanding of the struggle for emancipation in the Spanish colony and the island of Hayti or La Española as they provide lesser known background of new social actors, political loyalties, and realignments that came to the fore prior to 1822, the year when Haitian revolutionaries crossed over to Spanish Santo Domingo to unify the island. In a fascinating and at times cinematic account, Lora captures these two distinct political, cultural and ideological moments (1791-1804 and 1809-1821) interlocked by the aural sounds of Black freedom. Lora Hugi, the daughter of left-wing political exiles and artists, continues the work of radical historians by uncovering hidden collective memories and solidarities shared by Haitians and Dominicans as well as the meaning of freedom across time.

FURTHER READING

Lynne Guitar, “Documenting the Myth of Taíno Extinction”, KACIKE: The Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology [online journal],2002.

Teresita Martínez-Vergne, Nation and Citizen in the Dominican Republic, 1880-1916, Chappel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Anne Eller, We Dream Together: Dominican Independence, Haiti, and the Fight for Caribbean Freedom, Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

Lorgia García-Peña, The Borders of Dominicanidad: Race, Nation and Archives of Contradictions, Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

Nelson Santana, “José Mesón Acosta,” in Dictionary of Caribbean and Afro-Latin American Biography, ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Franklin K. Knight, New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Maja Horn, “Introduction: Critical Currents in Dominican Gender and Sexuality Studies in the United States”, Small Axe, 22 (2 (56)): 64–71, 2018.

April J. Mayes and Kiran C. Jayaram, eds., Transnational Hispaniola: New Directions in Haitian and Dominican Studies, Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2018.

Brendan Jamal Thornton and Diego I. Ubiera, “Caribbean Exceptions: The Problem of Race and Nation in Dominican Studies,” Latin American Research Review, 54(2), 413–428, 2019.

Anthony Stevens-Acevedo, The Santo Domingo Slave Revolt of 1521 and the Slave Laws of 1522: Black Slavery and Black Resistance in the Early Colonial Americas, New York: CUNY Dominican Studies Institute, 2019.

Amarilys Estrella, “Muertos Civiles: Mourning the Casualties of Racism in the Dominican Republic”, Transforming Antropolology, 28(1) :41-57, 2020.

Ana-Maurine Lara, Streetwalking: LGBTQ Lives and Protest in the Dominican Republic, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2020.

AUDIOVISUAL RESOURCES

Papa Liborio: El Santo de la Maguana documentary by Martha Ellen Davis

Salve para subir la voz song by Convite

12 de Octube: Nada que celebrar performance by several feminist and Afro-Dominican collectives

Espejos en las azoteas (1965) song by Mula

AUTHOR BIO

Amaury Rodríguez is a historian and translator originally from the Dominican Republic. He is co-editor with Raj Chetty of Dominican Black Studies (2015), a special issue of The Black Scholar journal.

Acknowledgments: The author would like to thank Marisol LeBrón and Evan Taparata for their invaluable comments and incisive editing. Special thanks goes to Nelson Santana, who revised an earlier draft; and Sarah Aponte and Martin Woessner for their generosity, insights and guidance.

[1] Rodolfo Kusch, Indigenous and Popular Thinking in América. Duke University Press, 2010. For background on Afro- Dominican thinking, see Martha Ellen Davis, La otra ciencia: el vodú dominicano como religión y medicina populares. Santo Domingo: Editora Universitaria, 1987.

[2] In June of 1963, in a speech at UASD public university, radical historian Hugo Tolentino Dipp (1930-2019) denounced the falsification of history and racism disseminated by the Trujillo regime while arguing for the need of historical materialist research. See: Hugo Tolentino, Origenes, vicisitudes y porvenir de la nacionalidad dominicana. Santo Domingo: Editora Enriquillo, 1963.

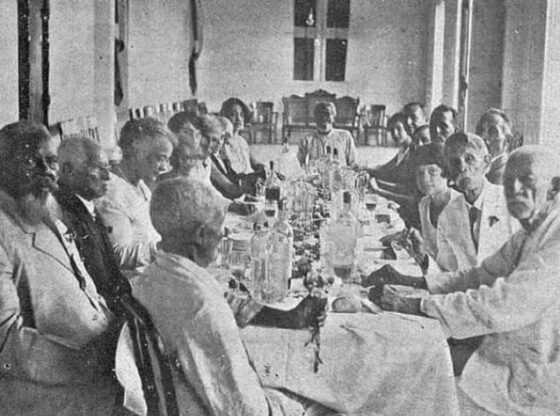

Veterans of the anti-colonialist war against Spain (1863-1865) at a dinner organized by feminist educator Ercilia Pepín (third in the left row) in 1927. Source: revista Blanco y Negro.

Veterans of the anti-colonialist war against Spain (1863-1865) at a dinner organized by feminist educator Ercilia Pepín (third in the left row) in 1927. Source: revista Blanco y Negro.