By R. Sánchez-Rivera

Recently, a published, peer-reviewed article caused a great deal of controversy when it circulated among many academic Facebook pages such as Latinx Scholars, Puerto Rican Studies Association (PRSA), and the Latin American Studies Association (LASA)-Puerto Rico Section. This article, “Economic Development in Puerto Rico after US Annexation: Anthropometric Evidence,” written by Brian Marein, a PhD student in economics at the University of Colorado, Boulder, brings together data to show that the average height of men in Puerto Rico increased by 4.2cm after the U.S. “annexation” (a euphemism for colonization). The author uses anthropometrics to argue that U.S. colonialism was actually beneficial to Puerto Ricans “in contrast to the prevailing view in the literature.” His main conclusion is that because U.S. officials brought in resources, food, and education, the life of Puerto Ricans improved (inferred by the increased height of men) as a result of colonization.

Anthropometrics refers to the measuring of people’s bodies and skeletons to correlate their difference to “racial” and psychological traits that privileged Eurocentric ideas of beauty, intelligence, ableness, morality, among others. This stems from a long history of “race science” that surged from the polygenetic assumption that (1) “race” was a biological type and (2) “races” had distinct origins. Two major theories of human origins and heredity dominated during the nineteenth century: monogenism and polygenism. Thinkers who advocated for monogenism argued that all humans came from the same origin but were in different developmental stages (usually with Whites at the top and Black people at the bottom). However, during the second half of the nineteenth century polygenism, or the notion that the “races” had separate origins and should be considered as distinct and immutable species, became more widely accepted.

These ideas of “race” had a significant impact on how scientific research developed as these methodologies became a way of legitimizing ideas that some groups should be colonized, enslaved, or eliminated. For instance, Philadelphia physician and polygenism advocate Samuel George Morton (1799-1851) measured and collected thousands of skulls to “prove” that some races were superiors to others. Morton was not an isolated case, however, as theories such as his were considered cutting-edge science. For instance, similar ideas were so widespread that they were supported by James Hunt (1833-1869), founder of the Anthropological Society of London; Hellen Keller (1880-1968); Winston Churchill (1874-1965), and Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), among many others. Thus, by having so many influential followers, “race” science cemented and structured the ways in which we think about racial difference in contemporary society. As Dorothy Roberts has stated, “race is not a biological category that it is politically charged. It is a political category that has been disguised as a biological one.”

Although born from the crucible of slavery and colonialism, it was not until the “Final Solution” and the genocidal atrocities committed by the Nazis during the Second World War that a widespread condemnation of “race science” (specifically eugenicist ideas) emerged. The 1950 UNESCO meeting was the first international attempt to stop using the word “race” and start using “ethnic groups.” Nonetheless, “racial groupings” remained as it was argued that there were three main categories of humanity: “(a) Mongoloid division; (b) the Negroid division; and (c) the Caucasoid division.” After receiving major international backlash, UNESCO issued yet another Statement on Race in 1951, with “ethnic groups” and “ethnicity” functioning as euphemisms for “race,” which could lead one to erroneously infer “that race and racial categories do not matter anymore”. Efforts to invisibilize the term “race” erased the long history of racialization processes and stripped away the language necessary to challenge racism. This is to say, while the term “race” started to “fall from grace” as a biological category, the UNESCO statement reinscribed the notions embedded in “race” science through a different terminological toolset.

By the late 1960s colorblind racism acquired a certain sense of cohesiveness and authority. Under colorblind racism, according to Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, “whites have developed powerful explanations-which have ultimately become justifications-for contemporary racial inequality that exculpate them from any responsibility for the status of people of color.” The existence of social inequalities rooted in a racializing assemblage that classifies people into categories of non-human, not-quite-human, and human now tends to be invisibilized inside of a seemingly post-racial society. Colorblind racism allows for the usage of methodologies and ideas developed during the period of “scientific racism” without using the terms that are now catalogued as a “pseudo-science.” These dynamics allow for the creation, maintenance, and resurgence of ideas rooted in scientific racism. For instance, in Marein’s article, he makes use of anthropometrics while disregarding the historical development of his theoretical framework and methodology by combining it with statistics and economics (both developed and tailored to better fit with eugenic ideas during the nineteenth century). Thus, the biggest challenge that we have is to find the tools and discourse to “call out” these instances of “covert” racism by looking at the continuities of racist practices that are structurally embedded in contemporary society.

Ideas and practices, rooted in “race” science, have been discussed and exercised after 1945, from Swiss experiments with eugenics (1920s-1960s) to the systematic targeting of indigenous populations for forced or coerced sterilization procedures in Peru during the late-90s. Thus, even if the language changed, practices, biases, and the construction of the “pathological” body remained the same. The archipelago of Puerto Rico is a great example for understanding the multifarious accounts of ideas and practices of “race” science that appear after the widespread condemnation of scientific racism. In Puerto Rico we see how the usage of “race” science by both US colonialists and criollo elites exacerbates social inequalities today.

Puerto Rico, a colony of the United States since 1898―and a colony of Spain for 400 years before ―was very much subjected, by the empires and local criollo elites, to eugenicist ideas. “Race” science, in the first-half of the twentieth century, allowed criollo elites to create new racializing parameters while inserting “progressive” measures of social hygiene, public health, and eugenics to promote ideas of modernization, progress, and civilization. These seemingly progressive ideas were cemented on the figure of “el jibaro” (a white Puerto Rican farmworker) as the mythical symbol of the Puerto Rican nation which is constructed as a product of the mixture of Black, indigenous, and Spanish. Discursively constructing Puerto Ricanness as the mixture of three “races” allows for an erasure of racialization processes and the systematic racist structure of Puerto Rican nationalism as an all-inclusive ideology of exclusion. The conflation of these three “races” to create a white/light-skinned farmworker signify an erasure of the “factors”/bodies that were assumed to compose the idea behind Puerto Rican nationalism. Additionally, by seeing these three “races” as a mere factor for the creation of the “jibaro” it invisibilized those bodies which—in the criollo elite’s views—did not belong unless they were to “better the ‘race”(an intrinsic eugenic idea rooted in popular belief around certain kinds of racial mixture “pa’ mejorar la raza”). Hence, Backness and Indigeneity in Puerto Rico are discursively mounted to create a seemingly mixed—dare I say, post-racial—society as long as Black and indigenous bodies mix and assimilate to the “jibaro nation.” This is to say, everything that falls outside of the national symbol of the “jibaro”—which strives for a lighter skin—becomes systematically pathologized. Hence, even if mixed-race identity is assumed to be the organizing principle, it is anti-Blackness and the systemic striving to achieve whiteness that operates as the driving force of Puerto Rican society.

Thus, “race” science in Puerto Rico played a pivotal role in the creation of discourses around modernization and progress among criollo elites that were then picked up by U.S. officials through colonialism. For example, during the first-half of the twentieth century a series of local and federal governmental educational campaigns advocated for the eugenic sterilization of Puerto Rican women, which resulted in a “twenty percent decline in population growth by the mid-1960s.” Additionally, by the 1950s and 1960s, Puerto Rico became the main site for the experimentations with contraceptive measures, such as “the pill,” which was initially envisioned as a eugenic measure for population control. Women used for these experiments were usually darker-skinned or Black and working-class and, and similar to medical sterilization practices (tubal ligation), they often did not have informed consent. In this sense, Puerto Rico became “the most important clinical site for testing the pill outside the national disciplinary institutions of the asylum and the prison and functioned as a parallel, life-sized biopolitical pharmacological laboratory and factory during the late 1950s and early 1960s. “Race” science and the racializing logics of criollo elites is what enabled the clinical testing of the pill by viewing it as a way to modernize Puerto Rico by following the U.S. model of a “small nuclear family” through population control measures.

Marein’s article disregards this long history of U.S. imperialism through anthropometrics to argue that after the U.S. “annexation” of Puerto Rico, the lives of Puerto Ricans improved substantially. The author uses anthropometrics to construct his argument without understanding and questioning the long history of scientific racism in the archipelago or in his own methodology. To clarify, I am not denying that there was an improvement in the living conditions of Puerto Ricans. The standards of living did increase, and many economists and public health officials have documented that but they also acknowledge that the picture is incomplete given the massive state reliance on population control (which he does not mention in his article) and the shedding of surplus populations through migration. Moreover, this was all done as a way to legitimize U.S. imperialism and assert their dominance as a power of the “West.”

Additionally, the article frames Puerto Rican migration as wholly positive, disregarding the human rights violations that Puerto Ricans encountered in the U.S. Thus, the notion that the “life of Puerto Ricans improved under US colonialism” signifies a systematic erasure of the violence that colonialism produces especially among those who are more vulnerable (like women, the working-class, Black Puerto Ricans, LGBTQI+ Puerto Ricans, and “disabled” Puerto Ricans, among others). Ultimately, this article furthers and legitimizes U.S. imperialism in the archipelago by arguing (with tools that stem from scientific racism) that Puerto Ricans should stop whining about our position as colonized subjects, instead we should be shilling for U.S. imperialism. This is particularly dangerous in our current moment when colonial rule is being fortified through measures like the implementation of the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico, which was created by the U.S. federal government under the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management and Economic Stability Act of 2016.

There are numerous “dangers” when it comes to writing such as Marein’s. There is the danger of normalizing the continued use of “race” science and anthropometrics in economic science. I think the affective reaction that many had to say that the article is racist is very legitimate. However, it is also incredibly important to understand where these logics stem from so we can fight the legacies of “race” science in “academic” research in this seemingly “post-racial” world. Lastly, I want to point out the fact that Marein’s anthropometric research on Puerto Rico has received funding from major institutions like the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Centre for Puerto Rican Studies (Centro at CUNY in New York), which is extremely worrying and should not go unnoticed.

AUTHOR BIO

R. Sánchez-Rivera is a historical sociologist and a sociologist of health and illness currently working in the Department of Sociology at the University of Cambridge. They obtained their BA in Political Science and History at the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus as well as a M.A. in Regional Studies—Latin America and the Caribbean from Columbia University in the City of New York. They got their Ph.D. in the Centre for Latin American Studies at the University of Cambridge, UK with a thesis titled “What Happened to Mexican Eugenics? : Racism and the Reproduction of the Nation.”

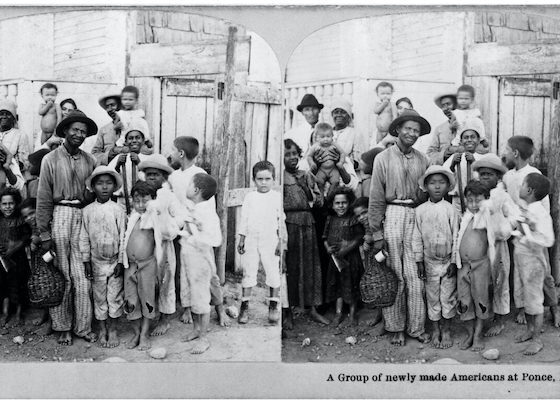

Pablo Delano, A Group of newly made Americans at Ponce, Porto Rico, (detail from the conceptual art installation The Museum of the Old Colony, 2016-ongoing). Source: Stereocard published by M. H. Zahner, Niagara Falls, New York, 1898. Photographer not identified.

Pablo Delano, A Group of newly made Americans at Ponce, Porto Rico, (detail from the conceptual art installation The Museum of the Old Colony, 2016-ongoing). Source: Stereocard published by M. H. Zahner, Niagara Falls, New York, 1898. Photographer not identified.