By Arlen Austin, Beth Capper, and Tracey Deutsch

This microsyllabus explores the activist and intellectual production of the International Wages for Housework (WfH) movement as a vital starting point for illuminating the history of our present. Today, after decades of neoliberal assaults on the racialized and gendered poor, we confront the unevenly distributed entanglements of care and social reproduction. Such uneven relations are only sharpened by the Covid-19 pandemic, which underscores the force of white supremacist, capitalist hetero-patriarchy on our material lives. The demand, for example, that we all “stay home” illuminates the brokenness of support systems for the precariously housed and homeless, those whose subsistence depends upon street economies, and those for whom the house itself is a site of sexual, racial, and gendered violence. The lack of infrastructure to support the elderly, ill, disabled, and those who care for them reflects a corporate and political commitment to only those lives and labors considered “productive.” Wages for Housework provides an opportunity to reframe economies as grounded in reproduction. Material survival and well-being require dramatic reimaginings of the family and care, beyond isolated households of struggling individuals.

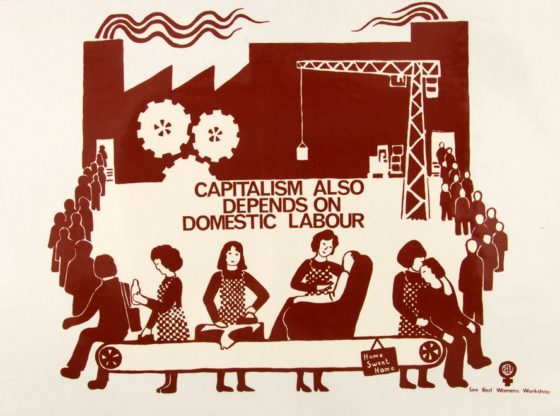

Wages for Housework generated influential thinking about how reproductive labor might be “counted” and organized on multiple fronts against the global capitalist system and for a radical vision of collective care. Although it never constituted a mass movement, branches of WfH were established on three continents. The political and theoretical understanding of its core members developed within anti-colonial, Black power, civil rights, gay liberation and workerist movements in North America, Europe and Africa. From this diversity of experience, members forwarded a feminist program attentive to the devaluation of reproductive labor or “housework,” which was grounded in the need for autonomous organizing cognizant of divisions within feminist and left movements.

This rich history of efforts to value reproductive labor provides resources for recognizing this work for what it is: crucial to all of our survival, at the absolute center of economies and exchange. In particular, this movement attunes us to how the devaluation of reproductive work sustains capitalism’s racial, sexual, and global hierarchies. It also attests to the ways in which actors on both the right and the left have disregarded, disavowed and rebuffed demands to take social reproduction and carework seriously.

In recent years, there has been a widespread reactivation of the perspectives and demands generated by WfH to confront ongoing crises of social reproduction. Moreover, “social reproduction” as a theoretical concept and terrain of insurgency has galvanized anthologies, manifestoes, special issues, and political actions attentive to the multiple and contested activist-intellectual genealogies that inform this term. We offer this syllabus as a contribution to these collective efforts to chart the terrain of social reproduction today.

This syllabus, like any syllabus, is necessarily incomplete. However, we hope that it provides some insight into the specific history of WfH as well as the range of scholarship and activism that has contributed greatly to our own understanding of social reproduction. We have situated WfH in longer and wider histories of social reproduction, as well as in relation to a contemporary surge of exciting feminist theory, history, and activism that has reclaimed care and reproduction as significant political forces and, importantly, arenas that demand and generate radical intellectual projects. We emphasize that valuing and refusing reproductive work requires movements with holistic, intersectional analyses. Centering reproductive work threatens everyday cultural “common sense” (eg, that “work at home” refers to a paid job rather than performing necessary tasks of daily life). It also threatens systems of race, sex and, by extension, capital. This microsyllabus reinforces two key tenets of the Wages for Housework movement – that the least visible work may be the most important, and that moments of duress and loss of autonomy can offer liberatory reimaginings of the everyday.

“We Can’t Afford to Work for Love” the first flyer produced by the New York Wages for Housework Committee and distributed in Prospect Park circa 1974. Silvia Federici Papers, Pembroke Center for Teaching and Research on Women, Brown University.

Resources on the History of the Wages for Housework Movement

The most comprehensive history of WfH to date has been compiled by Louise Toupin, a feminist scholar and original member of the Quebec Women’s Liberation Front, who affiliated with the WfH movement in the 1970s. Toupin’s work is particularly strong in contextualizing WfH in relation to second wave feminism and currents of the postwar global left. However, documents generated by the movement itself are powerful ways into its theoretical interventions. WfH focused on the role of reproductive labor in mediating the direct exploitation of the wage and the divisions of sex, race and class subtending the capitalist accumulation process. This was distinct from many Marxist and socialist parties, which privileged directly-productive industrial labor as the primary site of exploitation and fulcrum of transformation. A founding document of the movement, the “Statement of the International Feminist Collective” composed in the Veneto region of Italy in 1971, decried the contemporary left’s constricted conception of “class,” calling instead for an autonomous, global feminist network not restricted to wage laborers. In a key early text, “The Power of Women and Subversion of the Community,” Mariarosa Dalla Costa analyzed the subterranean, multi-faceted world of women’s work that was rendered invisible by the absence of the wage. She critiqued “labors of love” that were demanded by a sexual division of labor. Other essays and texts might be primarily associated with a particular intervention: Leopoldina Fortunati’s L’arcano della riproduzione: casalinghe, prostitute, operai e capital interrogated Marxian accounts of surplus value for their elision of reproductive labor; Selma James’s pamphlet Sex, Race and Class offered an influential analysis of intersectional and overlapping oppressions; Silvia Federici’s pamphlet “Wages Against Housework” served as one of the key manifestos articulating the movement’s overarching claims.

WfH insisted that failure to account for vast differences in experience and divisions in the distribution of labor along lines of race, class and sexuality would simply re-inscribe such divisions within the women’s movement itself; discussions of autonomy and difference within movement organization were especially crucial to the Wages for Housework program. Thus many contingently autonomous groups formed within the movement, including Black Women for Wages for Housework (BWfWfH), whose co-founder Wilmette Brown authored important texts on the autonomy of black lesbian women. Wages Due Lesbians (WDL), primarily based in Canada, composed insightful texts on the relation between lesbianism and the gendered distribution of labor, as well as issues of child custody. WfH also formed alliances with sex worker advocacy groups, such as the San Francisco-based group C.O.Y.O.T.E (Call Off Your Tired Old Ethics) and the English Collective of Prostitutes. Such collaborations made sex work pivotal to the theory and politics of reproductive labor.

At its height in the mid-1970s the group included branches in New York, London, Geneva, Berlin, Boston, and Toronto and engaged with the politics and organizational challenges of immigration. Alongside these archival documents, special issues of Viewpoint and The Commoner have foregrounded the relevance of historical WfH texts in the present. Additionally, both Camille Barbagallo and Arlen Austin (a contributor to this microsyllabus) have collaborated with members of the movement to produce new anthologies and essay collections. Also worth watching is All Work and No Pay, a 1975 film made by the Power of Women Collective and WfH groups based in the UK, which has been made available by the London Community Video Archive.

Laura Briggs, How All Politics Became Reproductive Politics (University of California Press, 2018).

The rhetoric of “Wages for Housework” resonates so strongly in our current moment largely because of neoliberal and conservative attacks on all forms of reproduction, including reproductive labor. Laura Briggs’ work draws a through-line that connects late 20th century conservatism and neoliberalism with today’s crisis of care, calling out unremitting assaults on homes and the unpaid labor that happens there. As Briggs argues, in the wake of neoliberalism “all politics became reproductive politics. Households are where we have most acutely felt the changes of neoliberalism, its shocks and disruptions.” Briggs’ narrative includes obvious insults to women’s care work (e.g., welfare reformers’ insistence poor mothers take paid work, as if the combination of household obligations and having to navigate countless bureaucracies to get housing and healthcare were not laborious enough). But Briggs’ expansive analysis also includes practices that might not obviously seem to impinge on care work (foreclosure, for instance). She powerfully documents how and why reproductive labor has become a “stress storm” for most Americans. And in so doing, she deftly skewers the argument that the fraying of households and families reflects an “elite” feminist desire for fuller lives and paid work. Rather, households struggled to shore up elder care, child rearing and education, and neighborhoods because of an upward redistribution of resources.

Angela Davis, “Reflections on the Black Woman’s Role in the Community of Slaves,” The Massachusetts Review 13: 1/2 (Winter-Spring 1972).

Verónica Gago, “#WeStrike: Notes toward a Political Theory of the Feminist Strike,” South Atlantic Quarterly 117: 3 (2018).

Contemporary re-engagements with the WfH movement and its intellectual production have reignited discourses of work refusal, and, specifically, the radical potential of the reproductive labor strike or work stoppage. Mariarosa Dalla Costa’s influential “A General Strike” and Kathi Weeks’ The Problem with Work: Marxism, Feminism, Anti-Work Politics, and Post-Work Imaginaries are key starting points for a deeper engagement with work refusal, and WfH’s contribution to its theorization. Here, however, we highlight two articles that speak to alternative, though resonant, explorations of reproductive labor as a site of resistance and refusal. In 1971, writing from the Marin County Jail, Angela Davis penned her essay “Reflections on the Black Woman’s Role in the Community of Slaves.” Although Davis’ text examines the multiple valences of black enslaved women’s refusals (from poisoning the master’s food to burning down the plantation house), she primarily focuses on the fundamental importance of black women’s domestic and caring labors for the survival of the enslaved community. By enabling this survival, Davis contends that black women’s reproductive labors themselves constituted a refusal of the slave system and a demand for abolition. In this sense, refusal is not simply the withdrawal of (reproductive) labor but is, instead, the redirection of this labor on behalf of black insurgency and autonomy. Davis wrote her essay while incarcerated and, as such, had very little access to historical sources to support her claims. For this reason, Alys Eve Weinbaum has described Davis’ account as a form of black feminist speculative history. Saidiya Hartman, herself a powerful deployer of speculative history, has also recently explored the political legibility of black women’s refusals of the slave system within historical discourses of abolition.

While Davis’ essay can be understood as rewriting the history of enslaved peoples’ insurgency from the perspective of black women and their reproductive labors, the International Women’s Strike has, over the past few years, worked to redefine the proper subject of “the strike.” The Women’s Strike emerged as a transnational movement in 2017, and was galvanized in part by large-scale feminist actions in Poland and Argentina the previous year, when women staged mass work stoppages (of both productive and reproductive labor). In “#WeStrike,” Verónica Gago, a scholar and member of Argentina’s Ni Una Menos collective, provides a theoretical reflection on the women’s strike within the context of contemporary feminist movements. Gago illuminates how the women’s strike fundamentally disfigures what constitutes a strike; it challenges what forms of activity count as “labor” and, indeed, “challenges the borders of labor” so as to encompass the struggles of the precarious, the devalued, and the unemployed. At the same time, she also contextualizes women’s strikes in Mexico and Argentina in relation to Latin American feminist movements against femicide, emphasizing the imbrication of violence against women with women’s laboring conditions. “#WeStrike” and a collaborative text by Gago and Ni Una Menos, “Critical Times / The Earth Trembles,” are part of two special sections on the women’s strike in South Atlantic Quarterly and Critical Times: Interventions in Global Critical Theory. These sections also contain dispatches from Italy, Mexico, Uruguay, and Turkey, among others, that place the international women’s strike in the context of both national and transnational struggles.

Jennifer L. Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004).

WfH members insisted that racial inequities were at the heart of reproductive inequity. This analysis was also an historical one, drawing on the longer history of capitalist and white supremacist practices that dehumanized black women by refusing to acknowledge their gendered labor. Jennifer L. Morgan’s research on racial slavery remains crucial to understanding this history. Morgan powerfully demonstrates that African and African American women’s ability to bear and rear children was crucial to the slave economy in North America and the Caribbean, and consequently their reproductive labors were crucial to the construction of racial categories. But importantly she also argues for the converse – that race governs the history of reproductive labor. To underscore this, Morgan’s reading of the colonial archive demonstrates how black women were characterized by their propensity to perform hard physical labor and reproductive work simultaneously. Such colonial depictions thus produced a racial division inherent to reproductive labor. Morgan’s is part of an essential body of work on black women and reproductive labor; her account is in conversation with arguments by Hortense Spillers and Saidiya Hartman that gender and reproduction in their normative idioms have been foreclosed to black women in the wake of transatlantic slavery. Sarah Haley’s work on the convict leasing system expands such arguments by considering the specific role of the carceral state in conscripting black women to labor “on both sides of the gender divide.” Like Morgan, these scholars also make clear the significance of reproduction and carework as a bulwark of black survival.

Premilla Nadasen Welfare Warriors: The Welfare Rights Movement in the United States (Routledge, 2005).

One of the movements most invoked and studied by members of WfH was the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO), emerging in the mid 1960s and largely based in grassroots organizing by black women on welfare. In Welfare Warriors, Premilla Nadasen expertly accounts for both the immense transformative potential and necessary limitations of the movement, which led to its dissolution. Nadasen utilizes the NWRO as a broader lens for troubling the boundaries that are often constructed in social movement history between women’s rights, poor people’s, and civil rights struggles in the 1960s and 70s. Throughout, she also calls into question the too easy dichotomies drawn between militancy and reformism in competing accounts of the movement, arguing that many demands that might be construed as reformist or liberal nevertheless “challenged the status quo for poor black women on welfare.” Alongside Nadasen’s book, Rosie C. Bermúdez’s work on Alicia Escalante and the Chicana Welfare Rights Organization deepens our understanding of the multi-racial coalitions formed within the movement. The original texts of the welfare rights movement also make for an engaging read, including its journal The Welfare Fighter as well as the compilation Welfare Mothers Speak Out: We Ain’t Gonna Shuffle Anymore. The latter collection highlights important Native American and Latinx contributions to its analyses. The emergent women’s liberation movement in the US foregrounded welfare rights with texts of the executive director Johnnie Tilmon that were published in the preview edition of Ms. Magazine as part of an effort to connect the struggles of the NWRO with the women of color feminist analytic of reproductive justice. This connection, however, was short-lived as the mainstream feminist movement gravitated towards a narrower conception of reproductive rights.

Neferti X. M. Tadiar, “Life-Times in Fate Playing,” South Atlantic Quarterly 111: 4 (2012).

Neferti X. M. Tadiar’s work pushes discourses of reproductive labor to account for the processes of indebtedness and surplusing that render migrant reproductive workers disposable within the contemporary global economy. In this article, Tadiar contends that capitalism profits from the lives and reproductive activities of migrant workers precisely by transforming them into waste. One example she provides, drawing upon her larger body of work, is that of migrant domestic workers from the Philippines. Filipina domestic workers, Tadiar argues, exchange not simply their reproductive labor but their entire “bodily being”and “life-times” – life-times that are consumed and “used up” even as they simultaneously extend and accrue value to the life-times of their employers (as well as the Phillipine nation via remittances). Indeed, the life-times of Filipina domestics, as well as those of many other migrants, are in effect already “spent” due to debts incurred as a condition of entry. However, here as elsewhere in her work, Tadiar refuses the complete subsumption of the lives and social practices of Filipina domestic workers by the capital relation, arguing that the everyday activities of Filipina social reproduction provide resources for an alternative politics. Also crucial to understanding the global export of Filipina migrant labor in its historical and political context is Rhacel Salazar Parreñas’ work, particularly her Servants of Globalization and The Force of Domesticity: Filipina Migrants and Globalization, as well as Alden Sajor Marte-Wood’s more recent exploration of Phillipine “reproductive fiction” and crisis.

Jessica Wilkerson, To Live Here, You Have to Fight: How Women Led Appalachian Movements for Social Justice (University of Illinois Press, 2019).

The rural women Jessica Wilkerson describes here echoed WfH activists’ demand that their caregiving labor be supported. Their vision of a world in which care was at the center of social justice movements and public policy illuminates the historical moment and intellectual impulses that also encompassed WfH. Wilkerson’s account thus broadens our understanding of the linkages among struggles for women’s liberation and economic justice in the 1960s and 70s, particularly when placed in conversation with the history of WfH groups and the welfare rights movement in the United States. Wilkerson argues that women’s leadership of Appalachian social movements reflected a class-based feminism that prioritized the needs of their rural, impoverished, communities. Largely, although importantly not entirely, white organizations demanded that state and local governments, nonprofits and War on Poverty programs fulfill basic needs around housing, food access and access to healthcare. Wilkerson’s research complements and contrasts with Keona Ervins’ Gateway to Equality: Black Women and the Struggle for Economic Justice in St. Louis. Ervins argues that black working-class women’s commitment to economic justice was constitutive of both labor and civil rights movements, expanding agendas and shaping campaigns.

Resources on Queer and Trans Social Reproduction

The recent explosion of theory and activism around social reproduction has been accompanied by robust efforts towards queering and transing the analytics of social reproduction and Marxist feminisms. However, a focus on social reproduction and care has long been an enduring concern in queer theory and LGBT activism. For instance, Cathy Cohen’s pathbreaking essay “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens,” which, in part, reframes the mother on welfare as a primary subject of queer coalition, offers a vital framework for articulating queer politics and social reproduction struggles. In this vein, Nat Raha’s more recent work on the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (S.T.A.R) and Wages Due Lesbians also attests to the coalitions that activists forged on behalf of queer and trans social reproduction and survival. One common thread within genealogies of queer and trans social reproduction is the centrality of non-familial and non-domestic support networks. For example, Chandan Reddy’s 1998 reading of Jennie Livingston’s Paris is Burning offers a compelling account of queer kinship within New York’s house ball culture, as well as a critique of the heteronormativity of (certain) Marxist feminisms. Alternatively, Kim TallBear’s “Settler Love is Breaking My Heart” draws on a longer genealogy of Indigenous kinship systems, demonstrating that monogamy, the nuclear family, and heteronormativity are central facets of what she calls “settler sexuality.” The toll and significance of collective care is also emphasized in Brendan McHugh’s and Stephen Vider’s explorations of care for AIDS patients and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s essays on disability justice; these thinkers speak to how illness and disability sharpen discussions of carework within queer and trans communities. Scholars such as Aren Aizura and Martin Manalansan have argued that accounts of the global division of reproductive labor are still too often tethered to binary conceptions of gender and heteronormative sexualities, offering reconsiderations of social reproduction by centering queer and trans migrant workers and the uneven dynamics of transnational surgical tourism. While much work in queer studies has focused on efforts to resignify and reimagine the home and the family away from its heteronormative underpinnings, various activist-intellectuals have renewed earlier feminist debates surrounding family and gender abolitionism. Sophie Lewis’ Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism Against Family is the most well known example of the case for family abolition, while Maya Gonzalez has written widely on the logic and abolition of gender; however, there is a wealth of other exciting work, much of which has so far unfolded in the pages of collectively published journals such as Pinko, on podcasts, and as part of conference panels.

BIOS

Arlen Austin is a PhD candidate in the Department of Modern Culture and Media at Brown University where his research focuses on postwar social movement discourse and the political economy of mass media. He is the co-editor with Silvia Federici of The New York Wages for Housework Movement 1972-1979: History, Theory and Documents.

Beth Capper is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Departments of English & Film Studies and Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Alberta from 2019-2021. She received her Ph.D. in Modern Culture & Media from Brown University in 2019. Her research is broadly concerned with the history and theory of feminist media and performance in relation to questions of labor, social movements, and the politics of aesthetics. Beth’s writing has been published in Art Journal, Media Fields, Third Text, TDR: The Drama Review, and GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. She is also assistant editor (with Rebecca Schneider) of a consortium issue of TDR on “Performance and Reproduction.”

Tracey Deutsch is Associate Professor of History at the University of Minnesota, where she teaches, researches, and engages in public discussion about gender, capitalism, critical food studies, and modern US history. Her publications include Building a Housewife’s Paradise: Gender, Government, and American Grocery Stores, 1919-1968 and several essays on the politics of consumption and provisioning. From 2016-2019, she was also the Imagine Chair of Arts, Design and Humanities, leading the “Thinking Food” initiative