By Yalile J. Suriel

Despite their current presence at nearly two-thirds of colleges and universities, campus police departments failed to garner much scholarly attention from historians for much of their existence. These forces have often been dismissed as “rent-a-cops,” peripheral to the university, and largely inconsequential. As a result of these misconceptions, campus police have fallen beyond the scope of historians of policing and higher education alike. Over the past decade, however, several incidents generated a new interest in excavating the history of these police forces.

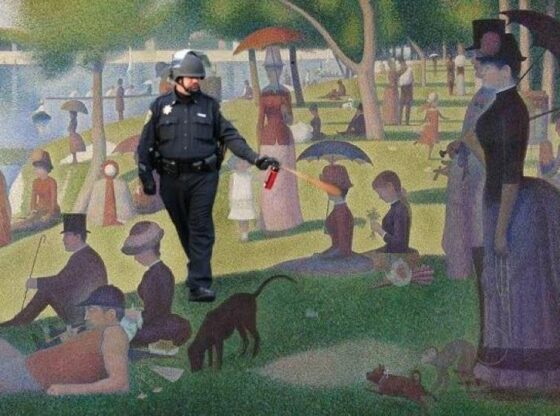

Across the country, national headlines have drawn attention to the consequences of having colleges and universities possess their own growing police apparatus. The 2011 pepper spraying of students at an Occupy protest by a UC Davis campus police officer prompted calls to investigate the role and function of campus police across the nation. The 2015 murder of Sam Dubose, a 43-year-old Black man who was pulled over for a missing license plate by a University of Cincinnati Police Officer, for instance, brought into focus the fatal consequences of expanding the jurisdiction of campus police beyond university gates. The 2020 revelation that the University of California at Santa Cruz used military surveillance technology to surveil a graduate student strike generated concerns about the weaponry available to campus police and their connection to the Department of Defense and military surplus programs. These examples are heavily featured in the works cited below and it was this type of media attention that mobilized, or in some cases reignited, decades of student activism that challenged the presence of police officers in university spaces. Indeed, for decades, student activists have been keenly aware of police presence on their respective campuses and have therefore engaged in a type of informal but powerful study of the suppression of protest by campus police well before it captured large scholarly attention.

While this new wave of activism was taking place, changes were afoot in several fields of study that provided the foundation for new scholarship on campus policing. The emergence of carceral state scholarship encouraged historians to see campus police officers within a carceral context, as part of the diffusion of policing that took place in the late 20th century, and as a new figure in policing worthy of analysis. Furthermore, changes within Critical University Studies, as succinctly explained by Eli Meyerhoff and Zach Schwartz-Weinstein in this microsyllabus, pushed scholars to “directly problematize race, gender, and coloniality.” The Critical University Studies microsyllabus, as well as Schwartz-Weinstein and Meyerhoff’s work — along with Abbie Boggs and Nick Mitchell –on abolitionist university studies is essential in understanding much of the work informing campus policing. Suffice to say that this move beyond Critical University Studies prompted the examination of campus police as a force that reproduces inequality within and surrounding universities. These massive historiographic shifts also encouraged historians of higher education to ask themselves how examining the role of campus police officers could enhance or reconceptualize our understanding of higher education in the United States.

Right now, in 2022, scholars across many disciplines are engaged in the project to better understand the history of campus police forces. Scholars are analyzing how these histories and their legacies shaped and continue to influence urban space, student activism, daily administration of colleges and universities, broader law enforcement policy, allocation of resources, city politics, and cultural discourse. Excavating the histories of these departments is no small feat, especially in a moment in which students are demanding increased transparencies from institutions, but often find their requests for information blocked. Organizers like CareNotCops and the Cops Off Campus Coalition have been deeply involved in not just uncovering information but also generating new visions of public safety within a university context.

This microsyllabus is designed to provide an accessible entry point into this emerging field of study. It highlights works that have profoundly shaped the scholarly landscape and provided the foundation for a new generation of forthcoming work. It also includes works in media such as podcasts and op-eds that contain the seeds for future research and center questions that scholars of campus policing continue to wrestle with. Most importantly, this microsyllabus should also serve as a reminder that our very own university archives are in need of further exploration. Equipped with the works below, new research can follow.

Davarian Baldwin, In The Shadow of the Ivory Tower: How Universities Are Plundering Our Cities, (Bold Type Books, 2021).

Baldwin’s groundbreaking work fundamentally revolutionizes how we think about universities and the cities they occupy. Baldwin draws our attention to how universities influence what is happening off-campus grounds and use their police forces as a tool of gentrification. This work examines how “universities exercise significant power over a city’s financial resources, policing priorities, labor relations, and land values,” resulting in a plundering of cities across the United States. Using the University of Chicago as one of his case studies, Baldwin shows how entire city blocks have been demolished in an effort to “fortify the campus from a perceived threat of Black and working-class residents.” Baldwin powerfully makes the case that “city schools can deploy the blunt force of campus police, along with the soft power of university amenities” to take over entire city blocks. For Baldwin, the issue of campus police is “a window into a deeper analysis of higher education’s broad political and economic impact.” In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower is a must read for anyone interested in campus police, higher education, and the transformation of urban space.

Grace Watkins, “ ‘Cops Are Cops’: American Campus Police and the Global Carceral Apparatus,” Comparative American Studies: An International Journal 17(3-4), 2020, 242-256.

Watkins opens an important new line of inquiry by pushing scholars of campus policing to think beyond the United States and to include a robust transnational analysis of empire. Watkins uncovers the previously unknown role that campus police officers played in constructing a global carceral apparatus and traces their efforts to legitimize themselves as “leading experts” on campus security. This article hones in on the professionalization efforts of campus police and excavates the exchange networks at work in the latter half of the 20th century.

Robert Chase and Yalile Suriel “Black Lives Matter on Campus– Universities Must Rethink Reliance on Campus Policing and Prison Labor,” in Black Perspectives, June 15, 2020.

Situated amidst the college student response to George Floyd’s murder, this short piece highlights the insidious intersections between an expansive carceral state and higher education. Chase and Suriel underscore how universities rely on exploitative prison labor and a capacious policing apparatus to maintain daily operations. The piece takes a closer look at student demands to have their respective institutions divest and re-think their connections to the broader carceral state.

Eddie Cole, “The Racist Roots of Campus Policing,” in the Washington Post, June 2, 2021.

In this short but powerful piece, Cole brings to the surface how “campus policing is rooted in conflicts between institutions of higher education and the Black neighborhoods near where they are often located.” Cole details how institutions like the University of Chicago, the University of Pennsylvania, New York University, and Temple University became influential voices in “urban renewal” policies that disproportionally displaced Black families and gave their university police departments the authority to police largely Black neighborhoods. In this snapshot, Cole makes clear the links between campus police and anti-Black violence.

John Sloan, “After Cincinnati, the big question: who are the campus police, anyway?” in The Conversation, August 3, 2015.

In this succinct piece, John Sloan provides an overview of a broad history of campus police departments and the issues sparked by the 2015 shooting of Sam Dubose at the University of Cincinnati. Works like this one are indicative of the shift that took place in the last decade in which the actions of campus police grabbed national headlines, prompting questions about their structure and scope. This piece connects the origins of campus police to ongoing debates about their existence. Sloan, who was an early pioneer of the study of campus policing, provided the foundation for the field with classic works such as: “The Modern Campus Police: An Analysis of Their Evolution, Structure and Function” in the American Journal of Police. For another accessible overview of the rise of campus law enforcement see: Melinda Anderson, “The Rise of Law Enforcement on College Campus” in The Atlantic, September 28, 2015.

Roderick Ferguson, We Demand: The University and Student Protests, (University of California Press, 2017).

The importance and impact of Ferguson’s We Demand cannot be overstated. Although it is featured and perfectly summarized in the Critical University Microsyllabus, it is so influential that it must be included here as well. Ferguson situates the emergence of campus police departments among the student activism of the 1960s and 1970s and pays special attention to the cooptation of student demands. Ferguson makes a compelling case that both diversity offices and campus police departments were part of institutional responses to student protest, purposefully designed to suppress and sidestep student demands.

The Activist History Review, November 2019 Issue on “White Supremacy in the University”

The Activist History Review’s issue on “White Supremacy in the University” features work on an array of topics including the struggle to remove confederate statues on campus, rename buildings, and overhaul tenure systems. Several pieces in particular focus on the issue of campus policing. Cobretti Williams’ piece “Race and Policing in Higher Education” sheds light on some of the tensions that administrators face when deploying their sprawling campus police departments. Blu Buchanan’s piece “A Black Class: Re-Learning Abolition in Higher Education Organizing” puts the struggle of Black labor organizing in conversation with the history of campus policing. Liz Coston’s piece “Buying Space, Policing Race” examines the overlap between campus police and city police as university real estate pushes deeper and deeper into neighborhoods.

Charles H.F Davis, Jael Kerandi, Nadine Jones, Wisdom Cole, and Marlon Lynch, “The Current State of Campus Policing” Lumina Foundation Podcast, October 19, 2021 and Charles H.F. Davis, Jude Dizon, Erin Corbett, Jael Kerandi, Heather Shea, “Campus Policing & Student Activism for Black Lives,” Student Affairs NOW Podcast, June 16, 2021.

The perspective of higher education scholars and administrators is an essential part of the campus policing story. In these podcasts, scholars, activists, and community members come together to discuss the state of campus policing and policy making within the university structure. Both podcasts highlight student voices, particularly that of Jael Kerandi, a former student at the University of Minnesota, who called upon the university administration to divest from the Minneapolis Police Department in the wake of George Floyd’s murder.

Teona Williams, “For ‘Peace, Quiet, and Respect’: Race, Policing, and Land Grabbing on Chicago’s South Side” Antipode 53(2), 2021, 497-523.

Williams innovative article sheds light onto the intersections between environmental justice, universities, and their police departments. Using the University of Chicago as a case study, Williams demonstrates how the university’s expansion into the surrounding neighborhoods result in struggles over the use of public spaces. University police are often called in response to these struggles, resulting in additional violence against Black local residents. This article offers a robust analysis of space, geography, and environment as it relates to campus police forces.

Dylan Rodríguez, ‘“Beyond Police Brutality”: Racist State Violence and the University of California,’ American Quarterly, June 2012, vol. 64, no. 2, 301-313 and Sunaina Maria and Julie Sze, “Dispatches from Pepper Spray University,” American Quarterly, June 2012, vol. 64, no. 2, 315-330.

Both of these articles examine the violence perpetuated by UC police. Using the pepper spraying of ten seated students by the UC Davis police at an Occupy protest as a launching pad, these works examine brutality and repression at the hands of campus police. These articles also provide an incisive analysis of police violence and situate expanding police budgets amidst the defunding of public education.

Scholars for Social Justice, Defund the Police, Webinar on Police, Race, and the University, June 2020.

In this webinar, scholars and student voices bring to light the key issues of campus policing, what we can all do about it, and how to navigate administrator cooptation. Scholars Davarian Baldwin, Barbara Ransby, Robin D.G. Kelley, and student organizers Michelle Yang and Kosi Achife offer their perspectives on how to imagine and envision a different university.

Grace Watkins, “The dark side of campus efforts to stop covid-19,” in the Washington Post, September 14, 2020.

As Covid-19 infection rates continue to surge and the nation’s campuses become hotbeds of exposure, Watkins’s article on campus policing and the efforts to mitigate Covid-19 remains salient. Watkins offers keen insight into how campus police are shaping the heart of student life and university operations during a global pandemic.

Lucien Baskin and Erica R. Meiners, “Looking to Get Cops Off Your Campus? Start Here,” in Truthout, and Student Nation’s, “What the Cops Off Campus Movement Looks Like Across the Country,” in The Nation.

Both pieces provide an important snapshot of organizing taking place at campuses across the nation. Together, they demonstrate that the history of campus policing cannot be written without centering student voices and urge all members of the university community (students, faculty, and staff) to recognize our collective ability to influence college and university policy.

AUTHOR BIO

Yalile J. Suriel is an Assistant Professor of universities and power at the University of Minnesota. She is working on a manuscript titled Campus Eyes: University Surveillance and the Policing of Black and Latinx Student Activism in the Age of Mass Incarceration, 1960-1990. Along with co-editors Grace Watkins, Jude Dizon, and John Sloan, Suriel is working on an upcoming edited volume titled Cops on Campus: Critical Perspectives on Policing in Higher Education. She is also the author of “What SUNY Albany Tells Us About the Policing of University Space” published in the Activist History Review.

"Spraying in the Park" (from "A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte" by George Seurat) One example of the "pepper-spraying cop" meme that became ubiquitous after the 2011 incident at UC-Davis that involved a campus police officer pepper-spraying a group of students sitting down in a line as part of an Occupy protest.

"Spraying in the Park" (from "A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte" by George Seurat) One example of the "pepper-spraying cop" meme that became ubiquitous after the 2011 incident at UC-Davis that involved a campus police officer pepper-spraying a group of students sitting down in a line as part of an Occupy protest.